An Open and Relational Take on Parables

Don’t Take the Parables Seriously No, Actually, Take the Parables Seriously

͐Micro Theology Series News

͐Recent Substack and Upcoming Substack Live Conversations

͐Today’s Post: An Open and Relational Take on Parables

͐Micro Theology Series News 🗞️

Well, here’s the good news: Each one of the four different books in my new micro theology series has seen time at the top of more than one new selling category on Amazon. Cool! If you have time, please consider writing a brief review.

Here’s the bad news: Somehow, I uploaded the incorrect interior for one of the books.🤦🏼♂️So, if you ordered my sexuality book in the first couple of days, you got the right cover but the wrong interior. You got eschatology instead of sexuality. Now, it’s possible that learning that there is no such thing as a rapture might give insight into your thoughts on sexuality, 😂 but this was not my intent. So, all that to say, if this was you, let me know and I’ll get you the right one.

͐Recent Substack Conversations 🎙️

Recent Substack live conversations (or sub-pods as

likes to call them) with around the microbiome and theology and around sexuality, flourishing, and open and relaitonal theology were super interesting. Plus, last week’s conversation with Maggie Rowe was fun. I hope you’ve had time to check them out. And our upcoming Substack conversation is this Friday, 1pm central with our friend, .͐Today’s Post: An Open and Relational Take on Parables 👇🏼

Don’t Take the Parables Seriously No, Actually, Take the Parables Seriously

More than once, I've heard the following from preachers or seminary professors regarding the parables that Jesus told: "They're important stories, but they can't really be used to form a theology." It took some reflection and lived experience, but eventually I realized why dominant religion in America feels the need to downplay the theology that emerges from these stories: The system is suspicious of parables because the parables give us reason to be suspicious of the system.

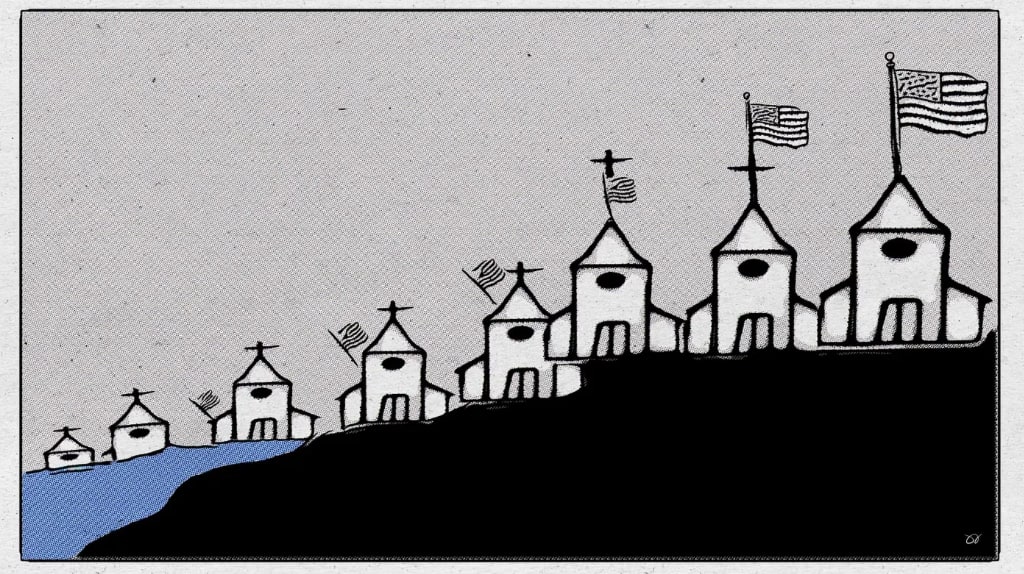

I tend to call this system Americanized-christianity. It's a hyphenated phrase with intentional capitalization to help communicate how empire modifies faith more than faith modifies empire. There are a variety of ways to characterize this modification, but here are three, plus a bonus. (Three, yea even four.)

The system is transactional rather than relational.

It sees through power rather than love.

It worships certainty above all else.

And crucially, it sees itself as beyond critique.

These modifications create a type of current. The Jesus stories flow in a different direction. The tension deepens because Jesus comes from within the system itself. Ha, the system knows that it should welcome one of its own, but the issues he are highlighting make it very difficult for the system to want to do so. It'd be like a corporation creating space for its lowest wage earners to reference the employee handbook, only to realize that their interpretations were undermining the corporation's power. 🤔

Consider Jesus, the representative of the powerless, telling The Prodigal Son story, with the way it reveals the insecurity of the dominant religious group (as represented by the older brother). The story infers that those who are lost can experience grace as much as—or more than—those who consider themselves found.

Or take The Good Samaritan story and the light it sheds not only on the importance of compassion, but on the way an outsider (in the form of the hated Samaritan) is more than capable of engaging in such behavior.

Then there's The Great Banquet story and the way it reverses religious-cultural expectations about who deserves to be honored.

Many, maybe all, the parables do similar kinds of things. They give us a matrix to run our theology through that keeps us honest, so to speak. Without such honesty, we run the risk of elevating our traditions, and the way they so easily funnel power to the top, above the kinds of things that are reflective of love. I actually think this is the kind of thing Jesus was getting at when he commented on the way the religious people were finding and using loopholes in the law to benefit themselves. He said they were "nullifying the word of God for the sake of their tradition."

This isn't to say that traditions in and of themselves are unimportant. On the contrary, traditions can serve an important purpose. (And obviously, much of what I'm doing in this writing is articulating my own tradition, influenced as it is by mimesis and open and relational theology.) But a religious system that cannot hold space for critique is doomed. A religious system that exists for the insiders more than the outsiders creates an unhealthy and even, dangerous context. This is, in many ways, why Jesus was crucified. And it's why, if you take his stories seriously, you will be in danger of something similar. I wish this weren't the case, but it is the reality, so proceed with caution. 😬

The Wheat and Weeds

One of my favorite parables, not for its warmth and fuzziness, but for its challenging message, is one that Matthew records. We sometimes call it The Parable of the Wheat and Weeds:

²⁴ He put before them another parable: 'The kingdom of heaven may be compared to someone who sowed good seed in his field; ²⁵ but while everybody was asleep, an enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat, and then went away. ²⁶ So when the plants came up and bore grain, then the weeds appeared as well. ²⁷ The servants came and said to him, "Master, did you not sow good seed in your field? Where, then, did these weeds come from?" ²⁸ He answered, "An enemy has done this." They said to him, "Then do you want us to go and gather them?" ²⁹ But he replied, "No; for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. ³⁰ Let both of them grow together until the harvest; and at harvest time I will tell the reapers, Collect the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned, but gather the wheat into my barn."' --Matthew 13

Open and relational theology gives us a three-fold framework to begin interpreting this story.

1. The God Jesus Talked About Didn't Control

It makes sense that Jesus didn't talk about a controlling God, because Jesus seemed very much committed to the concept of love. I suspect the healthiest thing one can do when referencing love is to keep it attached to words like consent, patience, and uncontrolling. Without these characteristics involved, we cannot call something love.

Think of it this way: Can you call it love when a parent forces their child to dress a certain way, controls how they talk, and is impatient with anything less than conformity? Probably not. Someone might say, "Well, the parent has a responsibility to keep their child safe." And that's true, but as every intellectually honest and loving parent knows, children must be allowed ever-increasing freedom to make their own choices as they grow. Love and freedom have a symbiotic relationship. (Hey, for healthy parenting stuff that I’ve benefited from, one should check out

or .)Freedom is good because it allows for the expansion of love, but freedom is challenging, for with an expansion of love comes the potential for risk. Or in the case of this parable, the potential for weeds. Who doesn't relate to the question these workers asked? Wait, where did the weeds come from? I thought someone good was in control here—how does something like this happen?

To engage these kinds of questions is to engage in what the world of theology references as theodicy, a term coined by the philosopher Leibniz that combines theos (God) and dike (justice). Theodicy revolves around the age-old question: "If God is perfectly good and all-powerful, why doesn't he prevent evil?"

And really, there were only two answers for the hearers of Jesus's story in his day … and … for those of us in our day: These things happen because God allows them to happen or because God is unable to prevent them from happening.

For most Americanized-christians, living downstream from centuries of Eurocentric, masculine, omnipotent theism, it seems obvious, given that God has all power and all control, that bad things can only occur because God allows them to occur. Never mind how disturbing or how out of alignment with love this might be.

Consider Karl Barth, the towering 20th-century theologian, who, to his credit, was open enough to name creation a risky move for God, "but a risk for which He was more than a match and thus did not need to fear." 🫡 Hmm, what does this mean exactly? Look, a risk with someone powerful enough to eliminate all fear isn't a risk. And if love doesn't risk, I don't think it can be called love.

Or listen to R.C. Sproul, the influential Reformed theologian who famously took no risks with a concept like risk. He wrote, "If chance existed, it would destroy God's sovereignty. If God is not sovereign, he is not God." And, memorably, "If there's one maverick molecule running loose in this cosmos beyond the scope of God's sovereign control and authority, you have no reason as a Christian to believe a single promise of the future that God has made." 🫡

No disrespect to Karl or R.C., but rather than trying to lock God into a tight predetermined box, I'd like to take a different approach—one that happens to resonate with both science and scripture.

Science recognizes indeterminacy, at least at the quantum level, as essential to life itself. Meanwhile, open and relational theology points to the scriptural commitment of a God of love—one that does not or cannot control. This means that sometimes things go badly, yes, because of human choices, or the reality of evil, and sometimes for no discernible reason at all. But if it's all unfolding within a context of love, then indeterminacy, chance, and risk are a part of reality.

Contrary to common pushback, this doesn't diminish God's power; it just reframes the question: What kind of power are we talking about? Open and relational theology says God's power is relational rather than authoritarian. 👈🏼

For example, who is stronger: the fighter George Foreman or the writer James Baldwin? If we're talking authoritarian, physical strength, then obviously it's George Foreman. But if we're talking about something deeper, more sustaining, and more enduring, there's no comparison.And that is what we're talking about here: something deeper, more sustaining, and more enduring... the depth of the thing... the depth of God. It's my contention that the depth of God is love, out of which all other attributes flow. And after years of my personal experience with deaths, murders, fires, diseases, and betrayals... it's the only thing that comes close to making sense. I think Jesus thought similar kinds of things about God, love, and power as well.

Particualarly, when you consider his Rich Young Ruler story (Mark 10:17-22), where he presents the rich man with a choice and then sadly watches him walk away. Jesus doesn't hound the man; he respects his decision, which would lead us to believe that God consents to decisions that people make.

Or his Parable of the Sower story (Matthew 13:3-23), where he describes the possibility of people responding to God in different ways—some hearts are hard, some shallow, and some choked by worries. It's clear that God has not predetermined the responses; no, there's possibility here.

Or in John 10:17-18, when Jesus says, "I lay down my life in order to take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down and authority to take it up again." It's more than reasonable to see him framing all this as a response to an invitation that itself could go a handful of ways, rather than following orders to march down one predetermined path.

So, how did the weeds get there? Jesus almost shrugs, "An enemy did it." I don't know about you, but this isn't my favorite answer. The problem of evil won't be solved with this parable. It appears that Jesus a) recognizes that sometimes things go sideways, b) that there is such a thing as an enemy, but that c) ultimately, God doesn't control all the outcomes.

2. The God Jesus Talked About Needs Help

If risk is real, it means that God cannot singlehandedly control outcomes. Maybe this idea is new to you, but it's not that controversial when you think about it, for God cannot lie, be unfaithful, or override someone's freedom. God cannot create a married bachelor, fabricate a square triangle, or, despite all his strength, produce a moral Las Vegas Raiders fan. (And if you need more help processing this idea, see

’s work, including the book, God Can't.)Since God cannot force things to happen, life becomes collaborative rather than controlled. In other words, love needs our help.

In the context of this parable, apparently what love needs—and I'll be the first to admit that I don't like this—is to refrain from immediately ripping all the weeds out, and instead, to live in and among the weeds. In this sense, love is looking to express itself in patience.

Despite the reality of 13.8 billion years of evolutionary patience, despite the patience of Jesus, despite our sacred text saying love is patient, christians are often remarkably impatient. This impatience belies our lack of trust and reveals how often we're motivated by controlling power instead of consensual love.

So, in this story, Jesus conveys the importance of endurance and patience. Having said that, he didn't pause mid-parable to offer ideas on how to make this happen, so maybe we should. Here are three ways to cultivate patience:

A. Breath

Beyond the growing amount of evidence that paying attention to breathing reduces stress, I'd bet that all patient moves are accompanied by either conscious or unconscious breath regulation.

Think about the last time you responded well during a difficult interaction. Mentally walk yourself through that response and notice how you were able to take a breath in that moment. (By the way, notice how you're slowing down and breathing even as you replay it in your mind.) Breathing cultivates patience, and patience is an expression of love.

B. Hug

Physical touch from someone you feel safe with can regulate your body and set you up for patience. A hug releases neurochemicals that help us stay grounded. (See what

Unfortunately, Americanized-christianity—especially the caucasian variety—hasn't done well integrating the spiritual with the physical. Put simply: we’re not very good with emobidment stuff. But paying attention to safe physical connection, and/or being aware of what the body is interacting with, is key, particularly as we're disassembling and reassembling the way our faith operates.

C. Gratitude

When you catch yourself complaining, immediately name something you're grateful for. This simple practice can recondition you to move away from scarcity thinking toward abundance. The point isn't to dismiss legitimate concerns, but to prevent you from getting stuck in cycles of impatience.

Yes, breathing, physical touch from safe people, and cultivating gratitude help set us up for patience. A disembodied Christianity is anemic Christianity. As my theologian/neuro-relational friend

observes, "We're living in an evolutionary mismatch. Our neural systems were shaped for rhythm, presence, and connection, but we now exist in systems built for speed, extraction, and survival." adds that "Deconstruction often privileges the mind: theology, philosophy, critique. But the body—where trauma lives—is rarely invited into the process."Patience practices help our mind and body stay in touch with each other as they were designed. And, in the context of the point here, endurance, self-controll, and patience is what Jesus was emphasizing.

3. The God Jesus Talked About Was Moving Things Toward Justice

Healthy christianity asks us to think with endings in mind. In a sense, what one thinks about the future informs the means by which they get there. Who would deny that a healthy future for humanity and indeed the whole cosmos would be justice, goodness, and redemption; therefore, the way to get there is to act justly, to do good things, and to be redemptive in our relationships now.

If we're not looking for it now, what makes us think we'll be looking for it later? Much transactional christianity has promoted the idea that all you really need to do is pray, show up to church a bit, give a little money, and that the real thing starts after you die.

But to do that not only misses the now, it might miss the fullness of life later, for if one acts hatefully, projects all of their problems onto the other, and engages in violence now, why would anyone think that they'll suddenly be different later? What happens to this kind of christian? I don't really know for sure, but I suspect that some will get into whatever the next dimension is and have such a withered heart that they won't recognize love there any more than they've recognized love here.

I admit, I haven't always known how to organize my thinking around justice. It's a hopeful, warm, and welcoming light, but there's no denying that it casts a big shadow, namely, that if being a Christian brings the assurance of God ushering in justice at some point in the future, well, what is S(H)e waiting for? Why not do it now?

This question is so pressing for me that I've been tempted to despair.😔 But what open and relational theology gives, with its idea of a love that genuinely cannot control, is also a love that genuinely never gives up. So, maybe, at some point in the future, creation will respond to love's invitation enough to usher in a depth of redemption beyond what my current imagination allows for. Maybe the light of justice will always be shining, with corresponding shadows, but maybe the shadows themselves will shrink in scope and intensity. (sigh… may it be so.) 🙏🏻

However this plays out, what's unavoidable is that the God Jesus talked about was actively engaged in moving things toward future justice. Honestly, some days, about all I can do is note this in my mind, take a breath, and try to live in the light of that hope.

Wrapping Up, Yes, Let Parables Do Their Destabilizing Work

Engaging with this parable, and all of the stories that Jesus told, means learning to live in and among the weeds, to cautiously extend our arms in a safe embrace, and to cultivate gratitude even when the harvest feels distant. It means accepting that our theology must remain humble enough to be surprised when grace shows up in unexpected places and through unexpected people.

As difficult as all of this is to assimilate and put into practice, I think these are the kinds of things that need to be incorporated into our theology (and our anthropology). So, don’t listen to the preacher when he minimizes the importance of parables. Have the courage to recognize that the stories Jesus told were about God's character, and also, who we might become when we allow that character to shape our own character. The parables don't just critique the system—they invite us to embody an alternative. In this way, the parables are a good, albeit dangerous, gift.

Some questions for you: What do you think? How does this help or frustrate you? What parable stands out to you as particuarly insightful? Why is this probably the greatest Substack post you’ve ever read?

I’m truly honored to be mentioned by you—especially alongside Chris Hanson and in such a rich, thoughtful post. Thank you so much!

"It means accepting that our theology must remain humble enough to be surprised when grace shows up in unexpected places and through unexpected people."