Magnets, Grief, and Love

Four quick announcements and then something on magnets, grief, and love.

1)Season eight of the jonathan_foster podcast just began with an episode around Mimetic Theory and Middle-earth and my author friend, Matthew Distefano.

2)ORTcon. In person. Tetons. July. Hope you can join us.

3)I talked indigo: the color of grief with my friend, Glenn on the What If Project Podcast recently. Hope you’ll check it out.

4)Speaking of indigo … if you’ve found my writing to be helpful, would you take a moment and leave a review? You don’t have to leave a long written thing; just something honest. Thanks!

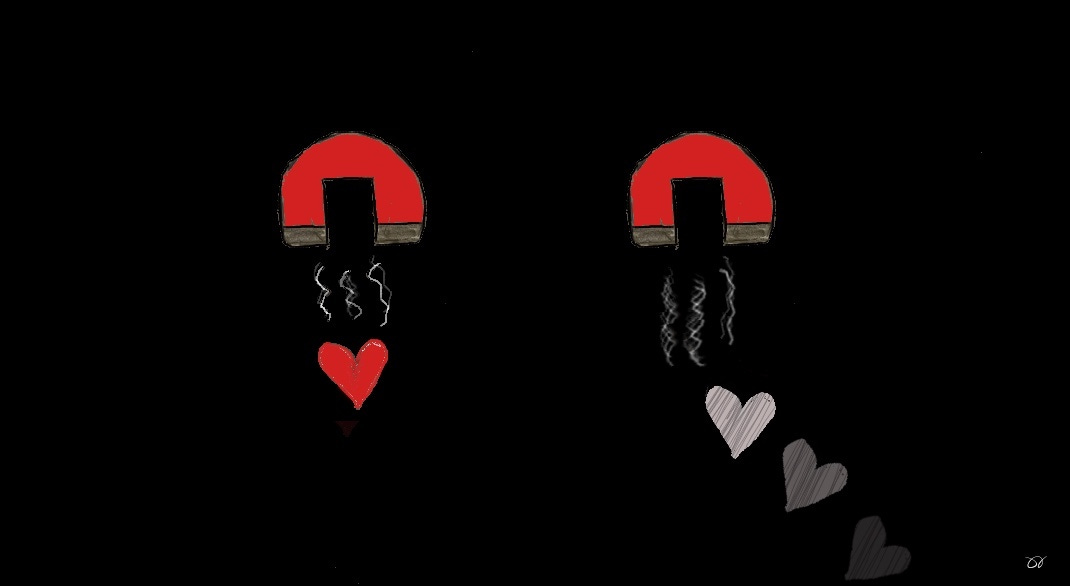

If a heart produces love like a magnet produces a magnetic field, then grief might be an unrequited magnetic field of love.

Unrequited magnetic fields of love

Unrequited magnetic fields of love mess with your identity … because there’s a gap where love used to bring two (or more) lives together. You feel your magnetic field of love sweeping out the gap, taking with it all the boundary markers that previously served to let you know who you were: father, friend, provider, teacher, helper, someone who could make someone laugh, etc. Love isn’t reciprocated in the manner it once was, so it kinda just spreads, or seeps, or fans out the gap into all kinds of places. It winds up being a terrible ache that goes everywhere, generally, because it’s a terrible love that goes nowhere, specifically.

Unrequited magnetic fields of love mess with your social life … because friends and acquaintances who haven’t had their North/South Poles all jumbled up? Well, they won’t really understand what’s happening to you. Not to suggest you really understand what’s happening to you, but after interacting with enough people in enough situations, you begin to discern that your magnetic field is messing with their magnetic field. And that’s a strange feeling. It’s not necessarily wrong, and people aren’t really to blame; it’s just strange—the intensity of your gap, out in the open, reminding them of the intensity of their gap they’ve worked so hard to keep hidden.

Unrequited magnetic fields of love mess with your theology … because, inevitably, all this gap-stuff leads you to think about God. You lay awake at night and stare at the ceiling as ill-defined ideas about omnipotence flit by in shadows, shifting and dancing momentarily before finding their way to the darkest corner of your bedroom. Everything rushes toward the gap.

What does God think of this gap?

Did God know about the gap?

Wait, does God have a gap?

After the fourth or twenty-seventh night of watching shadows, you start to think: maybe so … maybe this hole left by love is in some weird way reflective of the hole in the divine. And it makes you feel sick, or lost, or panicked because your theological construct is growing pixelated and dissolving (along with the way you’ve constructed meaning over the years).

But, in time, you start to feel something else. You start to sense something materializing amid all the pixelating, something more substantive: maybe the hole is still inside a kind of whole. Interesting.

In a kaleidiscopic kind of way, maybe everything is falling into itself. Perhaps this is the design. Or perhaps this how the design has adapted. Either way, it’s an injection of hope into your now fully-pixelated life, for the whole is still capable of holding you; still capable of holding everything. And while your definition of “holding” is different than it once was, you start to think, yes.

Yes

Getting to a yes is … well, you don’t know how to characterize it … it’s just the best. When you’ve spent so much time shaking your head in confusion, staring at ceilings in the dark, lamenting; when you’ve spent so much of your time screaming no, getting to the slightest possibility of a yes means everything.

Yes isn’t the one solid answer to all your questions. Yes isn’t even a solid. Yes is the smallest affirmation of faith as one is falling into the hole within the whole. Yes is the melody; better yet, the sounding of the melody, the movement of the melody. Maybe God is this that you’re trying to describe.

“Perhaps it can help to think and speak of God,” as your friend Jay McDaniel says, “as a gerund: a verbal noun. Perhaps God isn't different from the calling, perhaps God is the Calling.” Could the Calling encourage you to move forward, in faith, deep into the field of unrequited love? I suspect so. All of this is the melody of yes. McDaniel goes on to say, “The notes don't preexist their sounding; they are the sounding. God is godding and godding is God. This would be essential kenosis gerundified.”

Greiving still happens. The gap still exists. Your identity is still messed up; social life too. Everything’s been turned upside down, but yes keeps you going. It’s the possibility of something good still at play.

As you end the book indigo you say …

and now these two questions remain

why do bad things happen?

and why do good things happen?

but the greatest of these is

why do good things happen?